Korrelationer i R

Assessing Correlations

Correlation is a bivariate analysis that measures the extent that two variables are related (“co-related”) to one another. The value of the correlation coefficient varies between +1 and -1. When the value of the correlation coefficient lies around ±1, then it is said to be a perfect degree of association between the two variables (near +1 implies a strong positive association and near -1 implies a strong negative association). As the correlation coefficient nears 0, the relationship between the two variables weakens with a near 0 value implying no association between the two variables. This tutorial covers the different ways to visualize and assess correlation.

tl;dr

This tutorial serves as an introduction to assessing correlation between variables. First, I provide the data and packages required to replicate the analysis and then I walk through the ways to visualize associations followed by demonstrating four different approaches to assess correlations.

- Replication requirements: What you’ll need to reproduce the analysis in this tutorial.

- Visualizing relationships: Dots can tell you a lot about a relationship, so why not start with them?

- Pearson’s correlation: Measure the strength of the linear relationship between two variables. This approach is so widely used that when most people refer to correlation they are referring to the Pearson product-moment correlation approach.

- Spearman’s Rank correlation: A non-parametric approach that does not assume any assumptions about the distribution of the data. Great when variables are measured on an ordinal scale.

- Kendall’s tau: Another non-parametric approach. Less sensitive to outliers and more accurate with smaller sample sizes.

- Partial correlation: Measuring the relationship between two variables while controlling for the effect of one or more covariates.

Replication Requirements

This tutorial leverages the following packages:

library(readxl) # reading in data

library(ggplot2) # visualizing data

library(gridExtra) # combining multiple plots

library(corrgram) # visualizing data

library(corrplot) # visualizing data

library(Hmisc) # produces correlation matrices with p-values

library(ppcor) # assesses partial correlations

To illustrate ways to visualize correlation and compute the statistics, I will demonstrate with some golf data provided by ESPN and also with some artifical survey data. The golf data has 18 variables, which you can see the first 9 below; and the survey data has 11.

library(readxl)

golf <- read_excel("Golf Stats.xlsx", sheet = "2011")

head(golf[, 1:9])

## Rank Player Age Events Rounds Cuts Made Top 10s Wins Earnings

## 1 1 Luke Donald 34 19 67 17 14 2 6683214

## 2 2 Webb Simpson 26 26 98 23 12 2 6347354

## 3 3 Nick Watney 30 22 77 19 10 2 5290674

## 4 4 K.J. Choi 41 22 75 18 8 1 4434690

## 5 5 Dustin Johnson 27 21 71 17 6 1 4309962

## 6 6 Matt Kuchar 33 24 88 22 9 0 4233920

survey <- read_excel("Survey_Results.xlsx", sheet = "Sheet1", skip = 2)

head(survey)

## Observation Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q5 Q6 Q7 Q8 Q9 Q10

## 1 1 1 -1 1 0 1 1 1 0 0 0

## 2 2 1 -1 2 -2 1 1 0 0 0 1

## 3 3 0 0 3 -1 -1 0 -1 0 1 0

## 4 4 0 0 3 0 1 1 -1 0 1 1

## 5 5 0 -1 2 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1

## 6 6 2 1 2 -1 1 0 1 0 1 1

Visualizing Bivariate Relationships

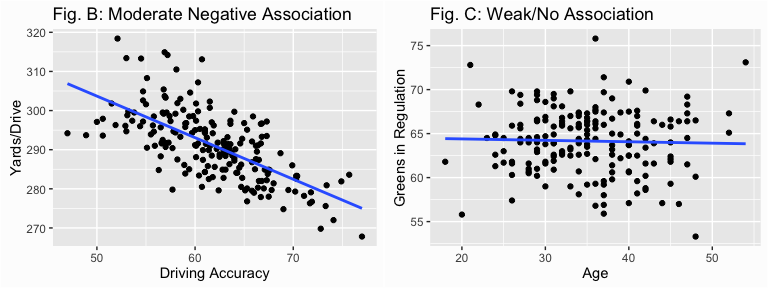

A correlation is a single-number measure of the relationship between two variables. Although a very useful measure, it can be hard to image exactly what the association is between two variables based on this single statistic. In contrast, a scatterplot of two variables provides a vivid illustration of the relationship between two variables. In short, a scatterplot can convey much more information than a single correlation coefficient. For instance, the following scatter plot illustrates just how strongly rounds played and events played are associated in a positive fashion.

qplot(x = Events, y = Rounds, data = golf) +

geom_smooth(method = "lm", se = FALSE) +

ggtitle("Fig. A: Strong Positive Association")

Contrast this to the following two plots which shows as driving accuracy increases the distance of the player’s drive tends to decrease (Fig. B) but this association is far weaker than we saw above due to greater variance around the trend line. In addition we can easily see that as a player’s age increases their greens in regulation percentage does not appear to change (Fig. C).

library(gridExtra)

p1 <- qplot(x = `Driving Accuracy`, y = `Yards/Drive`, data = golf) +

geom_smooth(method = "lm", se = FALSE) +

ggtitle("Fig. B: Moderate Negative Association")

p2 <- qplot(x = Age, y = `Greens in Regulation`, data = golf) +

geom_smooth(method = "lm", se = FALSE) +

ggtitle("Fig. C: Weak/No Association")

grid.arrange(p1, p2, ncol = 2)

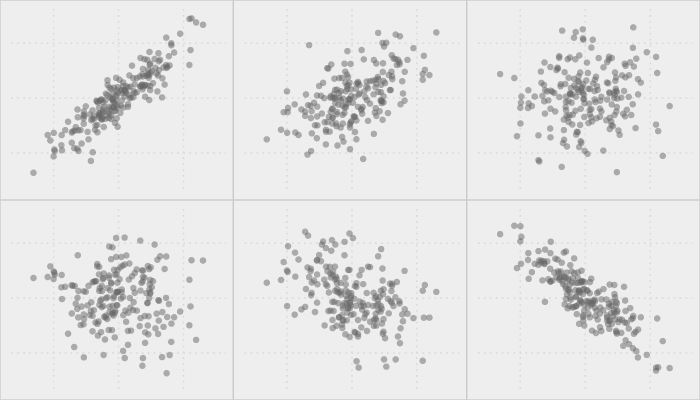

In addition, scatter plots illustrate the linearity of the relationship, which can influence how you approach assessing correlations (i.e. data transformation, using a parametric vs non-parametric test, removing outliers). Francis Anscombe illustrated this in 19731 when he constructed four data sets that have the same mean, variance, and correlation; however, there are significant differences in the variable relationships. Using the anscombe data, which R has as a built in data set, the plots below demonstrate the importance of graphing data rather than just relying on correlation coefficients. Each x-y combination in the plot below has a correlation of .82 (strong positive) but there are definitely differences in the association between these variables.

library(gridExtra)

library(grid)

p1 <- qplot(x = x1, y = y1, data = anscombe)

p2 <- qplot(x = x2, y = y2, data = anscombe)

p3 <- qplot(x = x3, y = y3, data = anscombe)

p4 <- qplot(x = x4, y = y4, data = anscombe)

grid.arrange(p1, p2, p3, p4, ncol = 2,

top = textGrob("Anscombe's Quartet"))

Visualization can also give you a quick approach to assessing multiple relationships. We can produce scatter plot matrices multiple ways to visualize and compare relationships across the entire data set we are analyzing. With base R plotting we can use the pairs() function. Lets look at the first 10 variables of the golf data set (minus the player name variable). You can instantly see those variables that are strongly associated (i.e. Events, Rounds, Cuts Made), not associated (i.e. Rank, Age, Events), nonlinearly associated (i.e. Rank, Top 10s), or categorical in nature (Wins).

pairs(golf[, c(1, 3:10)])

There are multiple ways to produce scatter plot matrices such as these. Additional means includes the corrgram and corrplot packages. Note that multiple options exist with both these visualizations (i.e. formatting, correlation method applied, illustrating significance and confidence intervals, etc.) so they are worth exploring.

library(corrgram)

par(bg = "#fdfdfd")

corrgram(golf[, c(1, 3:10)], lower.panel = panel.shade, upper.panel = panel.pts)

For corrplot you must first compute the correlation matrix and then feed that information into the graphic function.

library(corrplot)

cor_matrix <- cor(golf[, c(1, 3:10)], use = 'complete.obs')

corrplot.mixed(cor_matrix, lower = "circle", upper = "number", tl.pos = "lt", diag = "u")

Once you’ve visualized the data and understand the associations that appear to be present and their attributes (strength, outliers, linearity) you can begin assessing the statistical relationship by applying the appropriate correlation method.

Pearson’s Correlation

The Pearson correlation is so widely used that when most people refer to correlation they are referring to the Pearson approach. The Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient measures the strength of the linear relationship between two variables and is represented by r when referring to a sample or ρ when referring to the population. Considering we most often deal with samples I’ll use r unless otherwise noted.

Unfortunately, the assumptions for Pearson’s correlation are often overlooked. These assumptions include:

- Level of measurement: The variables should be continuous. If one or both of the variables are ordinal in measurement, then a Spearman rank correlationshould be conducted.

- Linear relationship: The variables need to be linearly related. If they are not, the data could be transformed (i.e. logarithmic transformation) or a non-parametric approach such as the Spearman’s or Kendall’s rank correlation tests could be used.

- Homoscedasticity: If the variance between the two variables is not constant then r will not provide a good measure of association.

- Bivariate Normality: Technically, Pearson’s $r$ does not require normality when the sample size is fairly large; however, when the variables consist of high levels of skewness or contain significant outliers it is recommended to use Spearman’s rank correlation or, at a minimum, compare Pearson’s and Spearman’s coefficients.

R provides multiple functions to analyze correlations. To calculate the correlation between two variables we use cor(). When using cor() there are two arguments (other than the variables) that need to be considered. The first is use = which allows us to decide how to handle missing data. The default is use = everything but if there is missing data in your data set this will cause the output to be NA unless we explicitly state to only use complete observations with use = complete.obs. The second argument is method =which allows us to specify if we want to use “pearson”, “kendall”, or “spearman”. Pearson is the default method so we do not need to specify for that option.

# If we don't filter out NAs we get NA in return

cor(golf$Age, golf$`Yards/Drive`)

## [1] NA

# Filter NAs to get correlation for complete observations

cor(golf$Age, golf$`Yards/Drive`, use = 'complete.obs')

## [1] -0.3960891

# We can also get the correlation matrix for multiple variables but we need

# to exclude any non-numeric values

cor(golf[, c(1, 3:10)], use = 'complete.obs')

## Rank Age Events Rounds Cuts Made

## Rank 1.0000000 0.2178987 -0.25336860 -0.39896409 -0.6340634

## Age 0.2178987 1.0000000 -0.11910802 -0.14056653 -0.1950816

## Events -0.2533686 -0.1191080 1.00000000 0.96635795 0.7614576

## Rounds -0.3989641 -0.1405665 0.96635795 1.00000000 0.8913155

## Cuts Made -0.6340634 -0.1950816 0.76145761 0.89131554 1.0000000

## Top 10s -0.8033446 -0.2052073 0.17710952 0.30790212 0.5255005

## Wins -0.5765412 -0.1753386 0.04591368 0.12215216 0.2460359

## Earnings -0.8585013 -0.2175656 0.15208235 0.29048622 0.5289126

## Yards/Drive -0.3008188 -0.3960891 -0.02052854 0.03470326 0.1465976

## Top 10s Wins Earnings Yards/Drive

## Rank -0.8033446 -0.57654121 -0.8585013 -0.30081875

## Age -0.2052073 -0.17533858 -0.2175656 -0.39608914

## Events 0.1771095 0.04591368 0.1520823 -0.02052854

## Rounds 0.3079021 0.12215216 0.2904862 0.03470326

## Cuts Made 0.5255005 0.24603589 0.5289126 0.14659757

## Top 10s 1.0000000 0.49398282 0.8957970 0.19397586

## Wins 0.4939828 1.00000000 0.7313615 0.21563889

## Earnings 0.8957970 0.73136149 1.0000000 0.25041021

## Yards/Drive 0.1939759 0.21563889 0.2504102 1.00000000

Unfortunately cor() only provides the r coefficient(s) and does not test for significance nor provide confidence intervals. To get these parameters for a simple two variable analysis I use cor.test(). In our example we see that the p-value is significant and the 95% confidence interval confirms this as the range does not contain zero. This suggests the correlation between age and yards per drive is r = -0.396 with 95% confidence of being between -0.27 and -0.51.

cor.test(golf$Age, golf$`Yards/Drive`, use = 'complete.obs')

##

## Pearson's product-moment correlation

##

## data: golf$Age and golf$`Yards/Drive`

## t = -5.8355, df = 183, p-value = 2.394e-08

## alternative hypothesis: true correlation is not equal to 0

## 95 percent confidence interval:

## -0.5111490 -0.2670825

## sample estimates:

## cor

## -0.3960891

We can also get the correlation matrix and the p-values across all variables by using the rcorr() function in the Hmisc package. This function will provide the correlation matrix, number of pairwise observations used, and the p-values. Note that rcorr() does not provide confidence intervals like cor.test().

library(Hmisc)

rcorr(as.matrix(golf[, c(1, 3:9)]))

## Rank Age Events Rounds Cuts Made Top 10s Wins Earnings

## Rank 1.00 0.21 -0.23 -0.38 -0.63 -0.80 -0.58 -0.86

## Age 0.21 1.00 -0.09 -0.12 -0.17 -0.20 -0.17 -0.21

## Events -0.23 -0.09 1.00 0.97 0.75 0.16 0.04 0.14

## Rounds -0.38 -0.12 0.97 1.00 0.88 0.29 0.12 0.28

## Cuts Made -0.63 -0.17 0.75 0.88 1.00 0.52 0.25 0.53

## Top 10s -0.80 -0.20 0.16 0.29 0.52 1.00 0.50 0.89

## Wins -0.58 -0.17 0.04 0.12 0.25 0.50 1.00 0.73

## Earnings -0.86 -0.21 0.14 0.28 0.53 0.89 0.73 1.00

##

## n

## Rank Age Events Rounds Cuts Made Top 10s Wins Earnings

## Rank 200 188 200 200 200 200 200 200

## Age 188 188 188 188 188 188 188 188

## Events 200 188 200 200 200 200 200 200

## Rounds 200 188 200 200 200 200 200 200

## Cuts Made 200 188 200 200 200 200 200 200

## Top 10s 200 188 200 200 200 200 200 200

## Wins 200 188 200 200 200 200 200 200

## Earnings 200 188 200 200 200 200 200 200

##

## P

## Rank Age Events Rounds Cuts Made Top 10s Wins Earnings

## Rank 0.0045 0.0011 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000

## Age 0.0045 0.1978 0.1084 0.0164 0.0056 0.0197 0.0041

## Events 0.0011 0.1978 0.0000 0.0000 0.0238 0.5953 0.0499

## Rounds 0.0000 0.1084 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000 0.0953 0.0000

## Cuts Made 0.0000 0.0164 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000 0.0003 0.0000

## Top 10s 0.0000 0.0056 0.0238 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000

## Wins 0.0000 0.0197 0.5953 0.0953 0.0003 0.0000 0.0000

## Earnings 0.0000 0.0041 0.0499 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000

Spearman’s Rank Correlation

The Spearman rank correlation, represented by ρ, is a non-parametric test that measures the degree of association between two variables based on using a monotonic function. The Spearman approach does not assume any assumptions about the distribution of the data and is the appropriate correlation analysis when the variables are measured on an ordinal scale. Consequently, common questions that a Spearman correlation answers includes: Is there a statistically significant relationship between the age of a golf player and the number of wins (0, 1, 2)? Is there a statistically significant relationship between participant responses to two Likert scaled questions on a survey?

The assumptions for Spearman’s correlation include:

- Level of measurement: The normal assumption is that one or both of the variables are ordinal in measurement; however, Spearman’s is also appropriate to use if both variables are continuous but are heavily skewed or contain sizable outliers.

- Montonically related: A linear relationship is not necessary, the only requirement is that one variable is montonically related to the other variable.

To assess correlations with Spearman’s rank we can use the same functions introduced for the Pearson correlations and simply change the correlation method. To illustrate, we’ll assess results from our artificial survey data in which the questions are answered on a 5 point Likert scale (Never: -2, Rarely: -1, Sometimes: 0, Often: 1, All the time: 2):

## Observation Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q5 Q6 Q7 Q8 Q9 Q10

## 1 1 1 -1 1 0 1 1 1 0 0 0

## 2 2 1 -1 2 -2 1 1 0 0 0 1

## 3 3 0 0 3 -1 -1 0 -1 0 1 0

## 4 4 0 0 3 0 1 1 -1 0 1 1

## 5 5 0 -1 2 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1

## 6 6 2 1 2 -1 1 0 1 0 1 1

To assess the correlation between any two questions or create a correlation matrix across all questions we can use the cor(), cor.test(), and rcorr()(Hmisc package) functions and simply specify method = 'spearman':

# correlation between any two questions

cor(survey_data$Q1, survey_data$Q2, method = 'spearman')

## [1] 0.3414006

# assessing p-value

cor.test(survey_data$Q1, survey_data$Q2, method = 'spearman')

##

## Spearman's rank correlation rho

##

## data: survey_data$Q1 and survey_data$Q2

## S = 3266.7, p-value = 0.06016

## alternative hypothesis: true rho is not equal to 0

## sample estimates:

## rho

## 0.3414006

# Correlation matrix and p-values across all questions

rcorr(as.matrix(survey_data[, -1]), type = 'spearman')

## Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q5 Q6 Q7 Q8 Q9 Q10

## Q1 1.00 0.34 -0.36 -0.09 0.31 0.31 0.24 0.30 0.25 0.35

## Q2 0.34 1.00 0.11 -0.22 0.04 0.01 0.21 0.59 0.32 0.14

## Q3 -0.36 0.11 1.00 0.13 -0.27 0.02 -0.12 -0.22 -0.16 -0.01

## Q4 -0.09 -0.22 0.13 1.00 0.23 0.17 0.17 -0.36 -0.13 -0.25

## Q5 0.31 0.04 -0.27 0.23 1.00 0.58 0.36 0.28 0.36 0.42

## Q6 0.31 0.01 0.02 0.17 0.58 1.00 0.33 0.31 0.33 0.63

## Q7 0.24 0.21 -0.12 0.17 0.36 0.33 1.00 0.27 0.24 0.12

## Q8 0.30 0.59 -0.22 -0.36 0.28 0.31 0.27 1.00 0.47 0.37

## Q9 0.25 0.32 -0.16 -0.13 0.36 0.33 0.24 0.47 1.00 0.39

## Q10 0.35 0.14 -0.01 -0.25 0.42 0.63 0.12 0.37 0.39 1.00

##

## n

## Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q5 Q6 Q7 Q8 Q9 Q10

## Q1 31 31 30 31 31 31 31 31 31 31

## Q2 31 31 30 31 31 31 31 31 31 31

## Q3 30 30 30 30 30 30 30 30 30 30

## Q4 31 31 30 31 31 31 31 31 31 31

## Q5 31 31 30 31 31 31 31 31 31 31

## Q6 31 31 30 31 31 31 31 31 31 31

## Q7 31 31 30 31 31 31 31 31 31 31

## Q8 31 31 30 31 31 31 31 31 31 31

## Q9 31 31 30 31 31 31 31 31 31 31

## Q10 31 31 30 31 31 31 31 31 31 31

##

## P

## Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q5 Q6 Q7 Q8 Q9 Q10

## Q1 0.0602 0.0498 0.6406 0.0877 0.0871 0.1923 0.1044 0.1837 0.0535

## Q2 0.0602 0.5630 0.2353 0.8327 0.9364 0.2553 0.0004 0.0800 0.4424

## Q3 0.0498 0.5630 0.4853 0.1418 0.9129 0.5375 0.2514 0.4129 0.9585

## Q4 0.6406 0.2353 0.4853 0.2117 0.3700 0.3473 0.0450 0.4890 0.1813

## Q5 0.0877 0.8327 0.1418 0.2117 0.0007 0.0489 0.1343 0.0444 0.0175

## Q6 0.0871 0.9364 0.9129 0.3700 0.0007 0.0671 0.0860 0.0669 0.0002

## Q7 0.1923 0.2553 0.5375 0.3473 0.0489 0.0671 0.1410 0.1895 0.5218

## Q8 0.1044 0.0004 0.2514 0.0450 0.1343 0.0860 0.1410 0.0070 0.0423

## Q9 0.1837 0.0800 0.4129 0.4890 0.0444 0.0669 0.1895 0.0070 0.0293

## Q10 0.0535 0.4424 0.9585 0.1813 0.0175 0.0002 0.5218 0.0423 0.0293

Kendall’s tau

Like Spearman’s rank correlation, Kendall’s tau is a non-parametric rank correlation that assesses statistical associations based on the ranks of the data. Therefore, the relevant questions that Kendall’s tau answers and the assumptions required are the same as discussed in the Spearman’s Rank Correlation section. The benefits of Kendall’s tau over Spearman’s is it is less sensitive to error and the p-values are more accurate with smaller sample sizes. However, in most of the situations, the interpretations of Kendall’s tau and Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient are very similar and thus invariably lead to the same inferences.

Similar to Spearman and Pearson, we apply the same functions and simply adjust the method type to calculate Kendall’s tau. Using the same survey data as in the Spearman example, we can compute the correlations using cor() and cor.test(); however, rcorr() from the Hmisc package (illustrated in the Spearman and Pearson examples) does not compute Kendall’s tau.

# correlation between any two questions

cor(survey_data$Q1, survey_data$Q2, method = 'kendall')

## [1] 0.3231124

# assessing p-value

cor.test(survey_data$Q1, survey_data$Q2, method = 'kendall')

##

## Kendall's rank correlation tau

##

## data: survey_data$Q1 and survey_data$Q2

## z = 1.9325, p-value = 0.0533

## alternative hypothesis: true tau is not equal to 0

## sample estimates:

## tau

## 0.3231124

Partial Correlation

Partial correlation is a measure of the strength and direction of association between two continuous variables while controlling for the effect of one or more other continuous variables (also known as ‘covariates’ or ‘control’ variables). Hence, it is used to find out the strength of the unique portion of association and answers questions such as: Is there a statistically significant relationship between driving accuracy and greens in regulation while controlling for driving distance?

Partial correlation can be performed with Pearson, Spearman, or Kendall’s correlation. Consequently, the assumptions required must align with the assumptions previously outlined above for each of these correlation approaches. The functions I rely on to analyze partial correlations are from the ppcor2package. To illustrate, let’s go back to the golf data I’ve been using throughout this tutorial. We may be interested in assessing the relationship between driving distance and getting to the green in regulation. A simple correlation test suggests that there is no statistically significant relationship between the two. This may seem a bit paradoxical because you would think players who can drive the ball further off the tee box are more likely to get to the green in less strokes. However, as we saw in the visualization section, those players who drive the ball further are less accurate so this could also be influencing their ability to get to the green in regulation.

cor.test(x = golf$`Yards/Drive`, y = golf$`Greens in Regulation`,

use = "complete.obs")

##

## Pearson's product-moment correlation

##

## data: golf$`Yards/Drive` and golf$`Greens in Regulation`

## t = 1.2591, df = 195, p-value = 0.2095

## alternative hypothesis: true correlation is not equal to 0

## 95 percent confidence interval:

## -0.05063086 0.22674963

## sample estimates:

## cor

## 0.08980047

If we want to identify the unique measure of the relationship between yards per drive and greens in regulation then we need to control for driving accuracy; this is known as a first-order partial correlation. We can do this by applying the pcor.test() function to assess the partial correlation between two specific variables controlling for a third; or we can use pcor() which provides the same information but for all variables assessed. The results illustrate that when we control for driving accuracy, the relationship between yards per drive and greens in regulation is significant. The simple correlation suggested an r = 0.09 (p-value = 0.21); however, after controlling for driving accuracy the first-order correlation between yards per drive and greens in regulation is r = 0.40 (p-value < 0.01). This makes sense as it suggests that when we hold driving accuracy constant, the length of drive is associated positively with getting to the green in regulation.

library(ppcor)

# pcor() and pcor.test() do not accept missing values so you must filter them

# out prior to the function

golf_complete <- na.omit(golf)

# assess partial correlation between x and y while controling for z

# use the argument method = `kendall` or method = `spearman` for non-parametric

# partial correlations

pcor.test(x = golf_complete$`Yards/Drive`, y = golf_complete$`Greens in Regulation`,

z = golf_complete$`Driving Accuracy`)

## estimate p.value statistic n gp Method

## 1 0.3962423 3.048395e-07 5.355616 157 1 pearson

What if we want to control for the effects of two (second-order partial correlation), three (third-order partial correlation), or more variables at the same time? For instance, what if we wanted to assess the correlation between yards per drive and greens in regulation while controlling for driving accuracy and age; then we just include all the control variables of concern (driving accuracy and age) in the z variable for pcor.test(). As we can see below, controlling for age appears to have very little impact on the relationship between yards per drive and greens in regulation.

# partial correlation

pcor.test(x = golf_complete$`Yards/Drive`, y = golf_complete$`Greens in Regulation`,

z = golf_complete[, c("Driving Accuracy", "Age")])

## estimate p.value statistic n gp Method

## 1 0.3802898 1.056049e-06 5.086053 157 2 pearson

Additional Resources

- Correlation: Parametric and Nonparametric Measures

- Fundamental Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences

- Discovering Statistics Using R

- On the Effects of Non-normality on the Distribution of the Sample Product-Moment Correlation Coefficient

- Anscombe, F. J. (1973). “Graphs in Statistical Analysis”. American Statistician, 27 (1): 17–21. JSTOR 2682899 ↩

- The

ppcorpackage also performs semi-partial correlations which I do not cover in this tutorial. ↩